I was five years old in a church when a woman stood to give the children a story. In the beginning, she asked, “What would you want to be when you grow up?” This is an embarrassing tale I have never told. There were a lot of us squeezed in a group of backless wooden benches in the front of the church just before the pulpit. My hand shot up first, I stood and with the microphone, I said, “I’d like to be a white person.” The congregation roared in laughter and the storyteller who had not expected this found some way to redeem my foolish utterance and continued with her story.

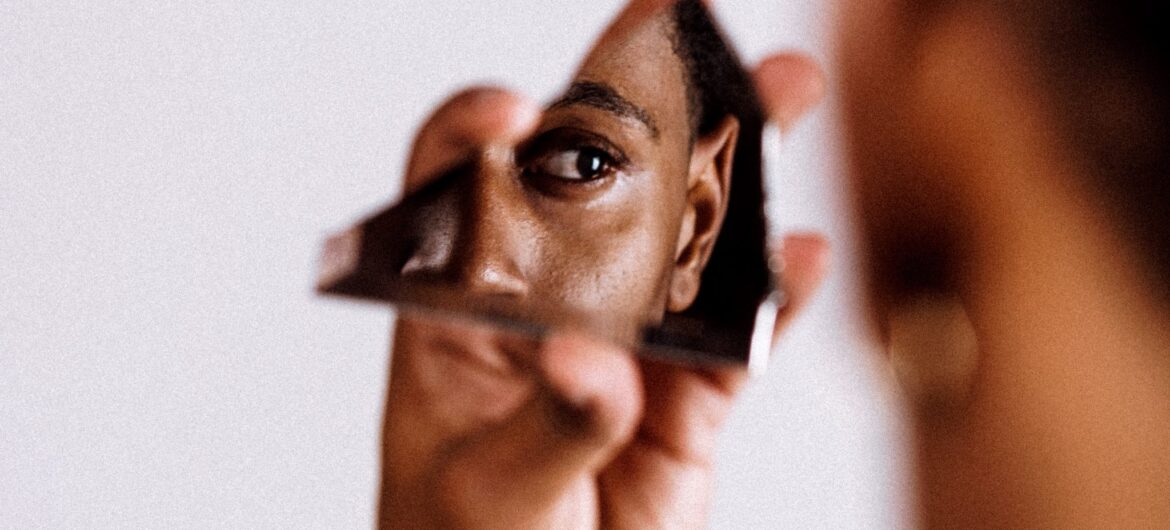

For a good few years it was just an embarrassing memory I never cared about. At some point, I was convinced I remembered it as having been said by another child that day until my mother brought it up with my siblings for a good laugh. After the thorough humiliation, it got me thinking about how at that age as an African child, I was convinced that there was another way to be. I did not fully understand the question posed because the concept of careers and occupations had not yet sunk in, but I knew I would be a better person if I grew up and became white. How that was going to happen, I had no idea, but in my five years of life, I was convinced there was nothing to love about being African or black.

For my friends in the township where I went home to sleep, this was a lane not meant for their feet to walk. That is why I understood their resentment and how I was an outsider even as we played together in the dusty streets.

Growing up during a tumultuous time in Zimbabwe, at the turn of the century, we all learnt that our society was very polarised on tribal and racial lines. My only memory of being in the same school with white children was in kindergarten, twin boys they were, and the last white pupils the school had. I do not know where they all went after that, but those that stayed would only be found in the most expensive and exclusive schools, mingling with those on their side of our polarised society. I went to “good schools”, my parents worked hard to make sure my sister and I went to the schools in town. In the afternoon when we would come back, our friends in the township would enviously jest about us going to “izikolo zamakhiwa” (the schools of the white people). These were the schools the white government had built, equipped and well-furnished, and from which the white kids had disappeared as soon as we started moving into them. But in these schools, us girls did not have to shave all our hair off as soon as it started to grow like our counterparts in the township schools, provided we permed it straight or “tamed” and hid it in plaits. We could play sports like tennis, hockey, rugby, basketball and even learn to swim at these schools. For my friends in the township where I went home to sleep, this was a lane not meant for their feet to walk. That is why I understood their resentment and how I was an outsider even as we played together in the dusty streets.

I doubt that there were many expressions of black beauty and celebrations of Africaness at the time. Women like Sandra Ndebele, Beatar Mangethe, Brenda Fassie and Yvonne Chaka Chaka were the idols that people loved and hated. They identified with them, loved their music, they related to the struggle and the stories their voices carried, but no one wanted their daughters to look up to them or grow up and be like them. These women were strong, expressive, confident and outspoken. The people in my society probably thought to themselves, “That’s no way for a black woman to be in the public eye, but it’s entertaining.” All we saw around us were women with hot combs, stinking perms and the rising trend of lightening creams. This is why at five, it was clear to me that even black people did not like being black because if they were not trying to adapt it, they were celebrating what it meant to them to be white. At least in my community. This why parents were proud of their children’s fluency in English over their mother tongue and why English names were the first given, otherwise, like some used to say in my township (directly and simply translated), “how are the white people going to call you.”

We did not love who we were, we were not taught how to. The story I told you, in the beginning, started to haunt me when I realised that I may have grown up to be a “white person”, at least in the eyes of my community and the kids that I grew up with. This realisation hits me every time someone (as some often still do) makes comments on posts of me handling a snake or any other animal. Playful jokes about my career being a white people thing mixed with fear and at times ignorance, which I approach with enthusiasm to educate. Have I achieved this very sad wish I had so long ago? Am I relatable to other young people like myself? Could I inspire them to pursue careers in science and nature conservation not just as rangers and guides telling tourists local names for things, but as researchers, decision-makers and policy enactors? I would like to believe that I can because our generation is breaking down the boundaries that used to separate us before. We are embracing the beauty of diversity and being who we are, knowing we can be whatever we want to be without having to change it. Part of it has been a process of learning to have uncomfortable conversations, share uncomfortable stories of the past and create new spaces that society cannot label black or white, this or that language, this or that class. Inclusion and representation are important for children to know they can be anything and achieve anything as themselves in a world to which they also belong.

Black birders week note:

Conservation in Africa has a face/race. This is not spoken of because it does not meet the bar of conversation in science, but it is widely known and it is the Achilles heel. This is not to say black people are actively excluded or discriminated against, however, it is harder to be a black person in conservation. In my short time in this field, I have been living between two worlds; my own, in which I have been socialised to believe the stereotype that loving nature is a “white thing”, which makes me a misfit among my people. The second one is my professional world, which believes black communities (largely) do not have an appreciation of the natural world and need to be taught. This offends me at varying levels. At times I am a foreigner in both worlds and I hope I can build a bridge between both worlds. Representation and inclusion are important for by-in. Natural resource conservation in Africa will only be effective when everyone believes they are a part of it and it will serve their collective interests. But this is a topic for another time…

blackbirderweek #blackinnature #blackwomenbirders #ornithology #birds #christiancooper amycooper #conservation #blacklivesmatter #blackwritters #blackvoices