TThere are still many questions left after Stellenbosch University announced that its shuttle fee has been “suspended”. Some of the short-term questions include whether the suspension is permanent, or just until after Woordfees. Also importantly, however, is the question of what happens next.

As was previously stated on iLizwi, the implementation of a fee for a service that was always free, aimed at those members of our community who are already the most financially vulnerable, is indicative of a particularly toxic neoliberal business-like institutional culture. Thus to be sure that any activism against the shuttle fee has been successful in the long-term, we need to see a change in the institutional culture, or at least a commitment to change. Whether this is in the form of an apology or a transparent proactive restructuring (preferably both) is up to management.

Unfortunately, students have received neither. Instead, the University has remained steadfast in their justification of the fee, with official communication almost patronisingly insisting that students rejected the fee “despite concessions”. This also raises the question of why the University had in fact suspended the fee if its justifications are so thoroughly believed throughout management. Two possible answers present themselves: 1. the justifications are not, in fact, recognised as valid throughout management, but rather seen as an unfortunate but necessary feature of the current state of the world, or 2. management is wisely cautious of upsetting the student corpus too much, lest they have another full-blown #FeesMustFall on their hands. (I suspect, perhaps optimistically, that the number of people who actually believe that the fee is a good thing is at a minimum.) The answer is probably a bit of both.

Moreover, throughout the entire debacle, management has been extremely recalcitrant in dealing with students. This reluctance was clear in their refusal to engage with protestors, opting instead to communicate only via the SRC. This is particularly problematic, as the SRC in its current form seems to only serve as the mouthpiece of management and not as a representative council of students. Management also refused to receive the People’s Movement’s memorandum after their legally recognised march to Admin B.

The goal of activism should be to challenge the conception of a status quo. This conception can either be normative or nihilistic: normative in stating that the fundamental principles that determine the structure of society are correct, stable and fair; and nihilistic in the admission that the fundamental principles are indeed wrong and / or unfair, but that nothing can actively be done about it. The way that activism should achieve this is by directly attacking both: the first through direct opposition, and the second through mobilisation.

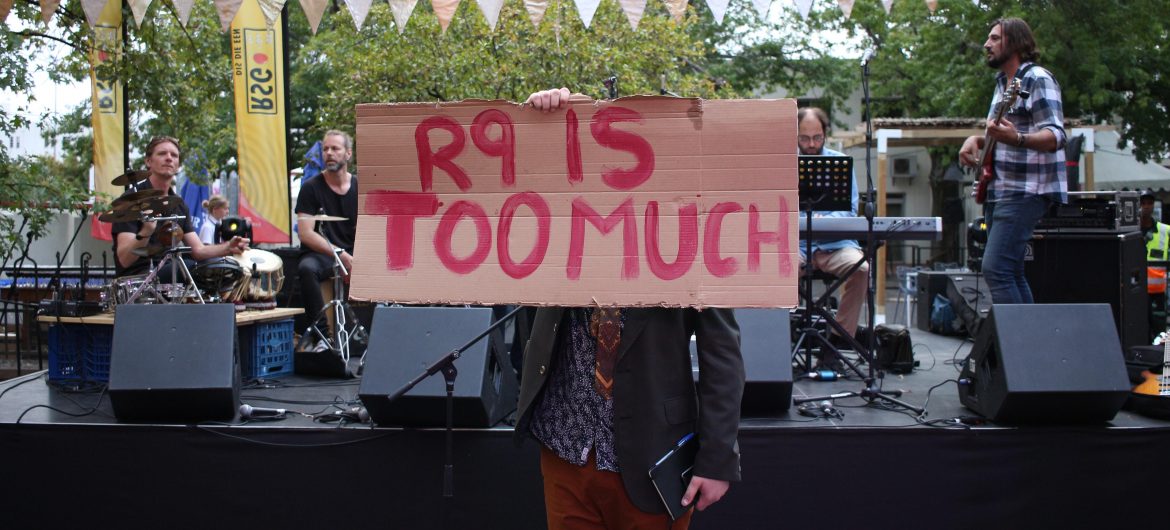

Protest movements aim to do both: by organising mass meetings and the march, the People’s Movement aimed to oppose management in their decision of the fee, but also to organise individuals who might have felt powerless into an effective structure.

As mentioned above, SU management wanted to defuse the situation, thus suspending the fee (permanently or not). This must not, however, be seen as a final victory for our activism — this concession is part of a strategy to keep the student corpus at an “acceptable” level of dissatisfaction which will keep them subdued. It does mean, in fact, that now is the time for engagement. Management must be pushed to explain how they will ensure this does not happen again.